New technological trends for carbon credit investors

Carbon credits are an essential part of the national and international scheme of things, which provides economic incentives worldwide to reduce pollutants and climate change. Thomas G. Giglione, founder and managing director of Carbon Credit Group in Toronto, writes on the potential of carbon credits and new technological trends.

Thomas G. Giglione, founder and managing director of Carbon Credit Group in Toronto

An influential annual report from British Petroleum on the future of energy said oil will be replaced by clean electricity from wind farms, solar panels, and hydropower plants as renewable energy emerges as the fastest-growing energy source on record. And one of the best-performing commodities at the moment is CO2.

According to the World Bank Carbon Pricing Dashboard, at the beginning of 2018, the price of European emission rights (the right to emit one tonne of CO2) was around €8 ($9.80), but now the price is already at €25 ($30).

According to the latest update from the International Carbon Action Partnership Secretariat on January 7, the Vietnamese Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MoNRE) should design a domestic emissions trading system (ETS) and prepare to participate in an international market from 2021, as well as promote Vietnam’s participation in international emissions trading under the Paris Agreement.

The Vietnamese National Assembly adopted the amendments to the Law on Environmental Protection last November that includes provisions for a domestic ETS, which is a market-based approach to controlling pollution by providing economic incentives for reducing carbon emissions.

Carbon credits are an essential part of the national and international scheme, which provides economic incentives worldwide to reduce pollutants and global warming. Carbon credits have turned into a market where businesses are buying and selling at prevailing prices. These credits can also be used to fund carbon reduction schemes between trading partners and around the world.

Basically, every organisation in a developed country has two ways to reduce the emission of greenhouse gases (GHG). Firstly, it can reduce GHG emissions by buying new technology or improving existing technology to attain the new norms for gas emissions. Usually, this is not recommended as it is very costly and will affect the economic situation.

Secondly, it can partner with developing countries and help them set up new, environmentally-friendly technology and earn credits. This is recommended because it is cheaper than many other expensive emission reduction projects in their own country.

Secondly, it can partner with developing countries and help them set up new, environmentally-friendly technology and earn credits. This is recommended because it is cheaper than many other expensive emission reduction projects in their own country.

The stakeholders for CDM projects include the project sponsor themselves; host countries; contractors; and public/private financial institutions.

For example, a company in Vietnam switches from coal power to wind energy, an activity that definitely reduces carbon emission. The CDM board then certifies carbon credits and as a result the company has reduced CO2 emissions by 100,000 tonnes per year. It is then issued with 100,000 Certified Emission Reduction (or CERs, commonly known as carbon credits). These can be sold to the companies unable to meet their developed countries’ targets.

Policy innovations

There is enormous potential for carbon credits to become increasingly lucrative. The world’s powers have thrown their weight behind incentivising decarbonisation in a last-minute sprint to meet the carbon curbing goals. The Paris climate accord set this to keep global warming limited to 1.5-2oC above the pre-industrial average.

Farming is one sector that produces a large amount of CO2. If a farmer removes CO2 from the atmosphere using crushed rock from mining or smart farming technology, it gets validated and recorded on the blockchain to trace the origin of the carbon offset to avoid the industry-wide problem of double counting. The technique would be straightforward to implement for farmers, who already tend to add agricultural lime to their soils.

Environmentalists are calling for policy innovation that could support multiple United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) using new advanced technology and government incentives to encourage the agricultural application of rock dust that could improve soil, farm livelihoods, and reduce CO2.

Income derived from carbon credit offsets from smart farming practices would help subsidised farmers to restore their soil health and pull CO2 out of the air. Research shows that adding rock dust from mining processes to farmland removes a significant amount of CO2. The chemical reactions that degrade the rock particles lock the GHG into carbonates within months, and some scientists say this approach may be the best near-term way of removing CO2 from the atmosphere.

Carbon Credits Group has also partnered with the Swiss company SOWAREEN SOLUTIONS to introduce Biochar to Vietnamese agriculture. It is a charcoal-like substance made by burning organic material from agricultural and forestry waste in a controlled process called pyrolysis.

During pyrolysis, organic materials such as straw as a byproduct of rice cultivation are burned efficiently in a tank with little oxygen. As the materials burn, they release little to no contaminating fumes. During this process, the organic material is converted into biochar, a stable form of carbon that cannot easily escape into the atmosphere. The energy or heat created during pyrolysis can be captured and used as a form of clean energy.

However, biochar is by far more efficient at converting carbon into a stable form, and it is cleaner than other forms of charcoal.

Smarter methods

Drip irrigation meanwhile delivers water and nutrients directly to a plant’s root zone, in the right amounts at the right time, so each plant gets exactly what it needs to grow optimally, when it needs it. It enables farmers to make higher yields while saving on water as well as fertilisers, energy, and even crop protection products.

By using this irrigation system, you reduce the impact of drought and climate change on food production; avoid contamination of groundwater and rivers caused by fertiliser leaching; and support rural communities by reducing both poverty and migration to cities.

If farmers switch to this drip irrigation system, then this man-made methane would lower to zero.

Employing best rice farming practices can also reduce water use by some 20 per cent and methane emissions from flooded rice fields by up to 50 per cent. It has been estimated that irrigated rice cultivation takes 30-40 per cent of the worlds’ freshwater, and it is a source of human-made methane emission.

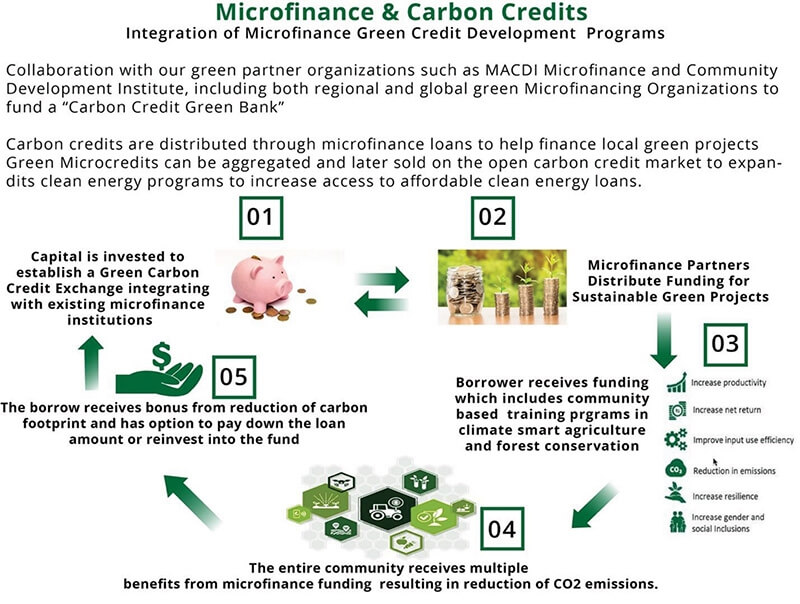

Another recent development in carbon credit trading is the integration of microfinance to fund smart farming projects to issue micro-credits. The Microfinance and Community Development Institute of Vietnam has recently entered a cooperation agreement with various stakeholders to attract capital investment for microfinance projects involving smart farming to reduce carbon offsets (see chart).

This is similar to a recent development project in Mongolia that combined microloans with the sale of carbon credits on the European Union ETS. The carbon credits would be generated by capturing reductions of greenhouse gas emissions.

The introduction of a possible carbon tax in Vietnam could also have an impact on the demand for and price of carbon credits, in particular in the voluntary market. The question is whether companies that fall under the carbon tax will also voluntarily compensate and whether carbon credits up to a certain level may be used as an alternative to tax.

For the voluntary market, much depends on the awareness of organisations and companies of the impact they have on the climate and the willingness to do something about it. Integration of voluntary carbon credits for airline passengers and introducing incentives using existing customer loyalty programmes would allow the average consumer to be involved in reducing their own carbon footprint.

There is an increasing number of companies that strive for climate-neutral or even climate-positive business operations, products, and services and the need to contribute to the SDGs.

As a result, it is expected that there will be a continuing need for high-quality climate projects in Vietnam, which also contribute broadly to sustainable development in the long term.